WORDS BY RACHEL RODDY

PHOTOGRAPHY BY NICHOLAS SEATON

Issue 2

Cooking Tails, Talking Tongues

A tale of two cuisines

WORDS BY RACHEL RODDY

PHOTOGRAPHY BY NICHOLAS SEATON

Tripe, pressed tongue, oxtail stew: gutsy, no-frills food was part of Rachel Roddy’s culinary upbringing, thanks to her northern relatives. Years later, she would find herself reconnecting with the traditional cooking she had tasted as a girl – in a quite unexpected place.

My Grandma Roddy made a good tea, a high tea. It would be ready waiting when the five of us arrived, crotchety after three hours in a hot car on the A1 from London to North Yorkshire. Phyllis’s teas were as dependable as her, and unchanging: bread (cut, ready and buttered), slices of boiled beetroot in vinegar, helpless lettuce, fruit cake or malt loaf with crumbling Wensleydale cheese, a jug of celery and, at the heart of it all, a pressed tongue. She would have prepared the ox tongue herself – boiling it, peeling it, then curling it like a sleeping cat in the round tongue press she had inherited from her mother.

I was never quite sure which was more formidable: the tongue, which looked so uncompromisingly like a tongue, or the iron press, which looked like a medieval instrument of torture. A clamp secured both the press to the Formica work surface and the plate on top of the tongue. Some hours of pressing later, a round a few shades less purple than the beetroot, was ready to be cut into slices. As a little girl I was fascinated by the swirling textures, and the thick, rich meatiness of each slice. I can recall one comment from my brother about eating tongue with his tongue but, other than that, the lettuce elicited more fuss.

There was ox tongue to be sandwiched between large white rolls that stuck to the roof of your mouth. Customers would help the sandwich along with a pint of Robinsons bitter

Meanwhile in Lancashire, my mum’s side of my family, represented here by my Aunty May, were still making oxtail stew or a meat and potato pie (possibly with the addition of a cow’s heel) in the kitchen of The Gardeners Arms, my granny’s pub. There was ox tongue in the pub kitchen too, though bought ready-cooked from the butcher, to be sandwiched between large white rolls called oven bottom cakes that stuck to the roof of your mouth. Customers would help the sandwich along with a pint of Robinsons bitter. The three of us, our legs swinging from bar stools in time to the jukebox, relied on R Whites lemonade, drunk from the bottle with a straw. In the same busy kitchen my Granny Alice would stew kidneys and skirt steak for a pie, and fry slices of lamb’s liver with onions for a favourite dinner (which meant lunch). "The slices must be thin," I can hear Alice saying with her soft but certain Manchester lilt.

Tripe wasn’t a regular ingredient by the time we three grandchildren came along, but it had been, and was referred to like an absent relative, with gossipy affection. I knew my dad’s side of the family ate tripe and something called slut served cold with vinegar. My mum remembered thick seam tripe cooked with onion in white sauce. Years later, recalling these conversations, I followed a Fergus Henderson recipe for tripe and onions and understood what my mum had meant when she talked about the tripe of her childhood being soothing. I was never tempted to seek out slut with vinegar.

They were meaty years, when we went up north at least, and it was all just ‘meat’, a slice of liver appreciated as much as a leg of lamb. It was everyday nose to tail, cooking born of necessity – little money and a war – though it continued even when things looked up, because it was good. There are other food memories too: custard tarts, Snowballs at the bar, crumble made with Timperley rhubarb, roast dinners served up on the studded brass tables when the pub was closed. But the memories of tongue, oxtail, kidney and liver are the most vivid. They are the tastes and textures I can recall with ease.

Things changed when Alice retired, when we drove up the A1 less and Grandma and Grandpa down it more, until they came south to live. Mum continued to cook liver and kidneys occasionally, but the rest – the tongue and tails – were no longer part of the way we ate, circumstances chipping away at tradition. The tongue press became a kitchen ornament on a high shelf. Once I had my own kitchen it crossed my mind many times to cook the things I had grown to like so much, especially when I read Jane Grigson, Elizabeth David, Simon Hopkinson and Rowley Leigh, all of whom can make a slice of tongue, sautéed kidney or breadcrumbed brain sound every bit as appealing as roast chicken. But in the end they had become things that crossed my mind, not my plate.

They were meaty years, when we went up north at least, and it was all just ‘meat’, a slice of liver appreciated as much as a leg of lamb

It was Rome that re-set everything. Ten years ago, I found myself living in a workaday part of the city called Testaccio, a word rather too close to ‘testicles’ for me in the early days. Located in the southern part of central Rome, and defined by a long, deep curve in the river, Testaccio is the city’s slaughterhouse district. At least it was, until the Mattatoio, Rome's main slaughterhouse and the heart of Testaccio’s economic life for almost a century, closed in 1975. The vast complex still endures, partly renovated and now occupied haphazardly. It includes a gallery, university faculty, the barely legal stables for the weary horses that drag carriages over Rome’s cobbles, and a wide open space where my young son runs wild.

I am reminded of the Mattatoio daily, as I can just about make out from my narrow balcony the statue of the winged god punching at an innocent bull above the old main gate. Enduring, too, is the other slaughterhouse legacy, quinto quarto cooking, which embraces the so-called fifth quarter, the leftover parts of the animal (tripe, oxtail, intestines, feet, testicles) which made up part of the slaughterhouse workers’ pay. Out of necessity and with characteristic Roman appetite, resourceful slaughterhouse wives forged good things from what they had. It is a tradition that lives on, thrives even, in the many trattorie in Testaccio, and many Roman homes.

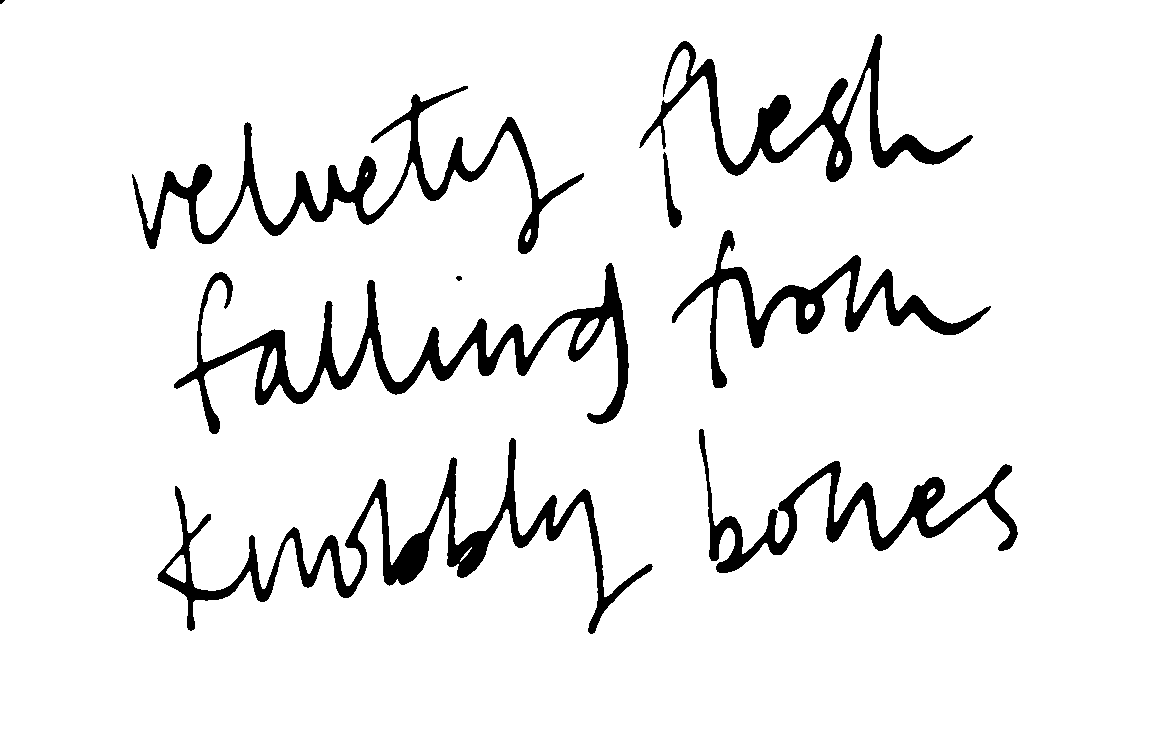

I began my quinto quarto education in a trattoria called Agustarello on Via Branca, a spare room of a place, which has since been smartened up, but not too much. Flick past the antipasti and stalwart Roman pastas and you will discover formidable-sounding secondi of which my Aunty May would have approved: tripe, oxtail, tongue, liver, sinews. I tentatively began eating my way through the menu, which was both familiar, and entirely unfamiliar, in this Roman setting. There was tongue with a sharp green sauce, tripe simmered in tomato sauce with Roman mint, served with a decent dusting of Pecorino Romano cheese, majestic oxtail stew, with velvety flesh falling from the knobbly bones, all of which left you sated and ready for a long nap.

After repeated visits and growing faith in Alessandro in the kitchen, I tried nervetti (veal sinews) for the first and last time. Also pajata, the intestines of milk-fed lamb, my initial response to which was similar to the slut, but with an added moral crisis. Eventually I made the leap and discovered that pajata, grilled with nothing more than olive oil, salt and pepper, are delicate and delicious – especially if sharing a plate with sweetbreads. I also discovered that I am happy to leave pajata in tomato sauce to others. In recent years Agustarello has been joined in my affections by Mordi e Vai, a stall on Testaccio market. Here, handsome, coiffed ex-butcher Sergio Esposito cooks up Roman classics and stuffs them into soft bread rolls. It was at this stall that I realised I adore tongue and tripe, so long as they are cooked well. I imagine Aunty May would have chosen both Sergio and his boiled beef sandwich; my Grandma Phyllis, with a bit of encouragement and the promise of a bench and a proper chat, would have gone for the tongue sandwich, with just a dab of green sauce.

Flick past the antipasti and stalwart Roman pastas and you will discover formidable-sounding secondi of which my Aunty May would have approved: tripe, oxtail, tongue, liver, sinews

For ten years now I have shopped at the busy market just minutes from my flat. Beyond the fruit, vegetables, fish and cheese, some ten butchers display tails and tongues, folds of tripe, glistening lamb’s heads that never lose their power to shock, next to rump and chops in equal measure. Then, back in my kitchen, I cook – inspired by what I eat here and by what my Roman friends and neighbours teach me. I am also inspired by what has come before, the cooking of my family in Lancashire and Yorkshire, the spirit of which seems kindred to Rome – by heck it does. I cook thin slices of Roman liver with onions, a smell that trans- ports me back to the pub. I turn oxtail into soup and cook tripe according to Granny Alice and to Fergus Henderson.

It was some time, though, before I cooked a tongue. I had forgotten how much tongue looks like a tongue: my brother was right. In place of a press, I used a bowl, two heavy books and an old-fashioned iron that usually serves as a door stop. I thought about Phyllis, her hardworking hands winding the clamp, and the heartening idea that you never cook alone, even when you are – that you cook with the person who taught you, be it a grandma, or friend, or author’s voice, with the generations who made that dish before you.

The makeshift press worked, almost. When it came to the tongue sandwich, though, the roll didn’t quite cut it: it wasn’t an oven bottom cake, and it didn’t stick to the roof of my mouth. I imagined an accompanying pint of Robinsons bitter, but a glass of functional Frascati – the sort that makes you shudder slightly – just about did the trick.