WORDS BY REBECCA MAY JOHNSON

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SOPHIE DAVIDSON

Series

A List of... Peas

Memories of eating

WORDS BY REBECCA MAY JOHNSON

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SOPHIE DAVIDSON

Every time we eat something we are also experiencing the memories of the last time we ate it, and the time before that, and the time before that... Hundreds of moments become crystallised in everyday objects, whether it’s a piece of toast, an apple, or a pint of milk. They may languish on shopping lists, but every edible is an archive. In this three-part series, Rebecca May Johnson writes a different kind of list, exploring the annals of memory contained in food.

I can tell my life in peas.

Standing in the supermarket freezer aisle, I remember the iron men and sometimes, I tell people about them. The iron men arrived in the dead of night. They came suddenly and from nowhere. When the iron men came the first time I didn’t know who they were. They were bigger than any animal or machine I had seen before. The iron men rolled fast onto the soft green field but it was dark and so the field was black apart from when their glassy eyes shot beams downwards and lit up green. The iron men came to take the green away. I could see that they were eating it from my bedroom window. They looked at it so they could kill it, I thought. The iron men moved like rank and file and swooped swooped swooped up and down, maws to the green and missing no square. They knew what they were doing. Tiny green limbs sprayed across the beams of light and mixed with midsummer flies.

In the morning it smelled of death. Sweet, becoming less so; heavy green sugar and a basenote of musk, growing stronger every moment. The tipping point of sweetness: rotting green skins turning to brown, the slow return to dust. A grubby plastic bag of peas in their pods would appear on the kitchen table the morning after, a gift from the farmer, a miraculous rescue from the night’s monstrous visitation. The sweetness amazed me and I thought about the peas pretty often the rest of the year. I don’t remember what we did with them other than eating a few from the pods. Probably my mother boiled them and served them with a touch of butter and salt and pepper. Probably we helped her pod them. Such a large pile of pods! So few peas! So much work! I softened. Of course they came so I could eat those sweet small peas in winter, pluck them from freezing obscurity and warm them again in my hand, boiling water, my mouth.

A grubby plastic bag of peas in their pods would appear on the kitchen table the morning after, a gift from the farmer, a miraculous rescue from the night’s monstrous visitation

The first time I noticed the pea harvesters, I was reading The Iron Man by Ted Hughes at school, the Faber edition with Andrew Davidson’s haunting illustration on the cover. Look it up: pure anguish, hollow eyes and loneliness. We saw the rock opera of The Iron Man on a special trip to London at the Young Vic theatre, with music by Pete Townshend from the band The Who. It was before Pete Townshend became a registered sex offender. It was the 1990s and my mother would put a handful of peas in macaroni cheese along with pieces of ham, sometimes sliced tomato on top. Peas were eaten with white things, and ketchup.

Learning how to use a knife and fork to eat peas in the way my parents wanted me to, aged around ten, I often thought of Ogden Nash’s nonsense rhyme "I eat my peas with honey; I've done it all my life. It makes the peas taste funny, But it keeps them on the knife." I tried to imagine the honey-pea combination and decided it would be horrid: two sweet things from different worlds I couldn’t fit together. It was hard to keep peas on my fork. I decided ketchup was a practical replacement for the honey.

Some of my best facts as a child concerned peas.

- The peas that grow around my house are Birdseye peas.

- Birdseye peas are harvested and frozen within two hours.

- Farmers grow peas as part of crop rotation because they put nitrates back in the soil, while wheat strips it out.

- Pea farmers operate in co-operatives so that if one of their pea crops fail they don’t go bust.

At 15 I got a job in the local fish and chip shop. I was paid £2.50 an hour, which rose to £3.80 after my trial period had finished. I wore a burgundy polo shirt branded with The Fish & Chip Inn that I left at work to be washed. I had to be driven to this job because we lived so far away from anything. When I came home every bit of me smelled of fish and chips, and after every shift I ate fish and chips which was heaven. I didn’t have mushy peas with my fish and chips then. They repulsed me.

The man who ran the chip shop was heavily involved in local amateur dramatics, the thought of which was slightly disturbing; at work he was pantomime friendly shot through with menace. I worked with women in their 20s who talked about people from the village I didn’t know and sex and told me to go on the pill and had scars on their arms from frying. They’d left the chip shop at various points and come back to it again. I wasn’t allowed to do the frying. I took orders and wrapped the food to take away. On the rare occasion that a customer decided to eat in the restaurant I served them food on plates. That happened so infrequently that it was stressful whenever it happened; I found it hard to remember all of the small procedures of service. I didn’t master much at all before I left. I couldn’t wrap the fish and chips in paper elegantly. It was a subject of embarrassment and frustration. My hot vinegary bundles sagged or crumpled and looked like they might collapse and spill chips and fractured pieces of fish. My physical clumsiness was mirrored by my poor social skills at work. I was shy and withdrawn: I didn’t know how to talk casually and my words sounded forced – they were.

I couldn’t wrap the fish and chips in paper elegantly. My hot vinegary bundles sagged or crumpled and looked like they might collapse and spill chips and fractured pieces of fish

Families and teenagers from the village would come in to get dinner. I served scraps, Pukka Pies, saveloys (arse and eyeballs, I’ll never forget that line), battered sausages, pineapple fritters, curry sauce, gravy and mushy peas, and of course battered fish. Defrosted fish taken out of the big fridge was filleted and dipped in rice cones then batter. The term "rice cones" fascinated me: I imagined tiny cones carved from rice. In fact it’s rice milled into coarse flour to encourage the adhesion of batter. When the frying oil was cold it looked like white greasy wax. I wanted to stick my finger in it but I never got the chance. It melted to a crystal clear yellow and got up to 400ºC in the fryer. When it was quiet we’d batter and deep-fry anything we could think of: cakes, pickled onions, sweets. How many inventions have arisen from such boredom? Out the back there was a chipper that fed into an old bath. A freshly chipped potato has an unmistakable creamy smooth texture inside, and a fresh flavour that cannot be had from a powdery frozen chip.

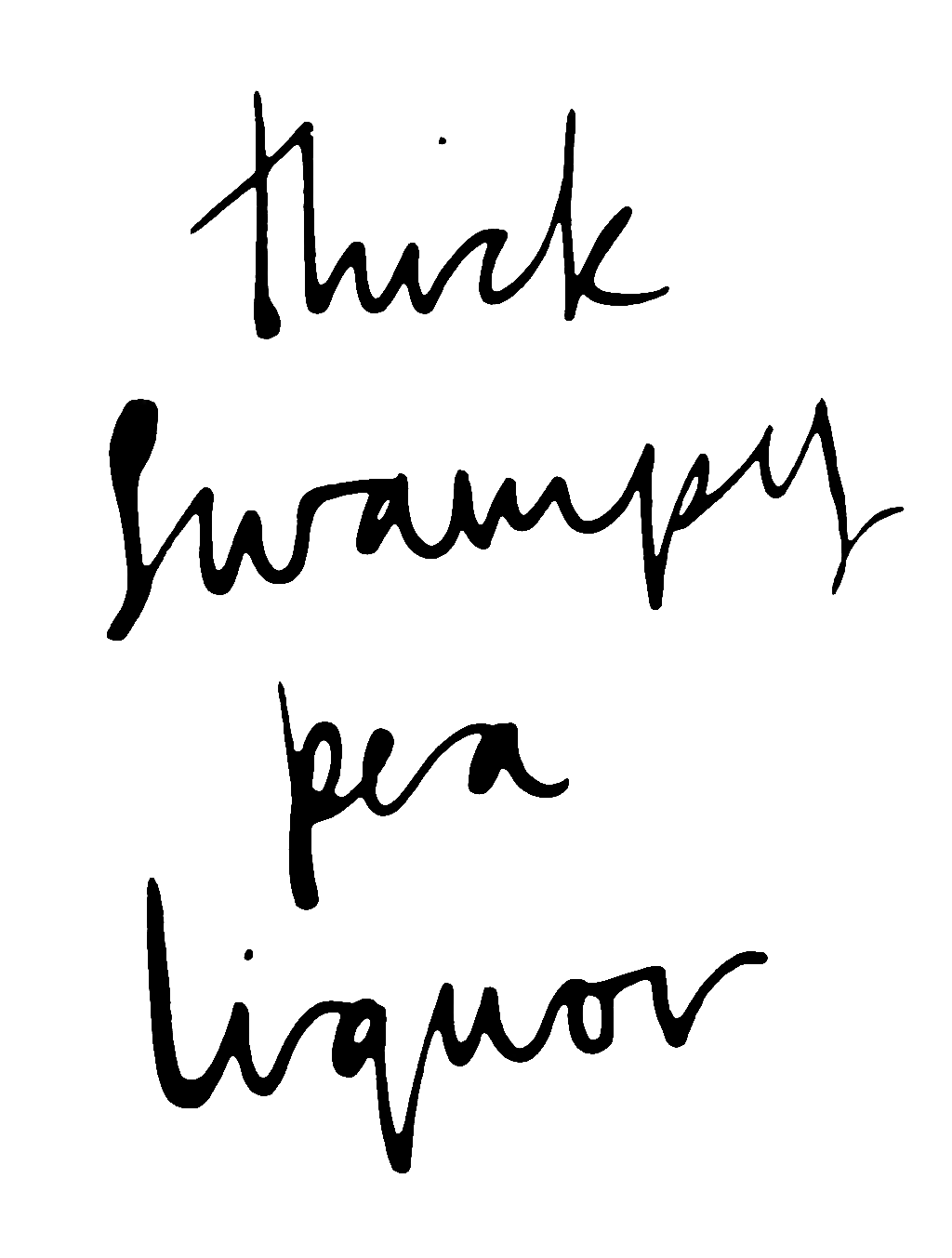

The end of each night was defined by peas: cleaning the stainless steel serving containers, scraping off dried-out pea liquor from the surface, wondering where the peas were in all the thick swampy liquor. I found out that mushy peas are made from marrowfat peas, a variety that is allowed to grow bigger than the petit pois sold by Birdseye. The marrowfat peas are left on the vine to dry out and then are soaked and boiled with sugar and bicarbonate of soda, and most that you get in chip shops have colouring added to brighten their green. The word marrowfat repulsed me as I imagined bones and animal fat were somehow involved in producing mushy peas. This association, even if I suspected it wasn’t accurate, lasted a long time. Now marrowfat peas are used to make wasabi peas too.

In March I began this digression into peas when, confused, I paid an awful lot of money for a small bag of peas in pods for a special dinner. Something didn’t feel right: I remembered the British air felt warmer when I last had fresh peas as a child. I realised that my brown paper bag held an imported luxury from Italy. Somewhere in Italy it was warm enough for peas in March. In July, the unpodded peas are £1.50 a bag in the seasonal British produce section in Sainsbury’s, still a lot for a handful of peas. Peas as therapeutic luxury: pod by hand, just a few.

Peas hover between everyday banality and magic. Peas are repetitive. If I have eaten one pea, I have not had peas; I couldn’t fathom peas from one pea. Imagine trying to pod enough peas by hand to eat for a full meal, before mechanical pea harvesters. The madness of peas is exposed in the early twentieth century play "Woyzeck" by Georg Bí¼chner. A doctor pays a poor man called Woyzeck to experiment on his mental health. He instructs Woyzeck to eat nothing but peas for three months. No reason is given for this. Have you eaten your peas, Woyzeck? You must eat nothing but peas! It seems hilarious, at first. So many silly peas! Nothing but peas! Ha ha ha ha! Accordingly, Woyzeck’s mental health deteriorates. Imagine the mad, desperate, Sisyphean fiddle of trying to pod enough peas to sustain your life. Along with various other cruelties (humiliation, his lover’s defection to a higher status man, being spoken about as if he were not present) the forced and repetitive consumption of peas transforms Woyzeck into an animal who consumes feed, rather than food.

You’re losing your hair, Woyzeck. Have you been pulling it out again? Don’t worry, man, it’s only the peas... (To his STUDENTS) Peas, gentlemen! Observe the creature, sustained by nothing but peas!! A revolutionary diet...

Peas hover between everyday banality and magic

Woyzeck’s peas reveal the acute and intimate violence of controlling what someone eats. He loses autonomy over what enters his body and he can’t afford to change his situation, he loses hope, becomes violently inhuman in his behaviour. The absurd horror of only peas forces a serious contemplation of gastronomic pleasure as essential to sanity, to happiness and to human dignity. Woyzeck shows us the effects and affects of food poverty and the politics of who eats, and what.

I have often relied on peas to feed me: pasta with peas, rice with peas, poached egg with peas, pea salad with lettuce, a combination of all of the above, with peas. Buying peas when I have money, forgetting about them, and finding them when my bank account is empty is an unconscious practice of saving myself. The mechanisation of the pea harvest means I can enjoy sweet and perfect peas at any time, and that no-one must re-enact the labours of Woyzeck, podding like mad, for maddeningly little reward.

~

The biggest bag of frozen peas I ever bought was to place behind my best friend’s dad’s back. It was so he could drive to her mum’s funeral, which came too soon. He drove, lying almost horizontal, after hurting his back in the panic to leave on time. The vital, ice-cold peas numbed the pain and allowed him to do the hour-long drive.